· winning · 12 min read

Reflection and Logging Outshines Planning

What if the key to achieving your goals wasn’t planning ahead, but looking back? This was the lesson I learned through years of tracking progress in fitness and productivity.

Originally written Sep 26, 2020. Last Updated Jan 8, 2025.

My athletic journey across American football, martial arts, powerlifting, and track and field, spanned over a decade and exposed me to a multitude of strength and conditioning programs, diets, and exercise regimens.

There was a point in time where I was doing a more intense phase of bodybuilding from the tail end of high school leading into my first few years of college.

Whether in bulking to put on muscle mass or in phases of cutting, the key that accelerated my progress more than anything was to log and take record of everything, almost obsessively so. I picked this up about 6 years ago (~2015) from Brandon Carter, a popular entrepreneur in the fitness industry.

The idea was simple: In order to gain actionable knowledge on which factors account most for your progress or lack thereof in the gym, log everything.

- Track daily water consumption down to the milligram.

- Take note of the food you put into your body and how much time you’ve spent sleeping each night.

- Track the sets, reps, and exercises done in your workouts.

- Maybe add a note about how you were feeling and when your energy levels were best.

- Measure your biceps, calves, thighs, waist, neck, forearms, etc. and record your bodyweight at least once per week.

It sounds extreme if it’s the first time you’ve heard about a strategy like this. I assure you, this technique works. By taking a meticulous record of all of the factors that impact your goals, you’re better able to assess what needs to be changed to get your desired outcome. You know when to add and take away calories, if your hydration is off, whether or not you’re stretching enough to prevent injuries, if certain foods are strongly affecting your energy levels.

I tried this approach for a few months and found huge success when I was bulking up from weighing 185 to 205 lbs. I added 80 lbs to my 1 rep squat max and 35 to my bench because of consistency and tweaks I knew to make from keeping a training log.

Planning vs. Reflection

I believe that one of the main reasons this approach is effective is that it takes the emphasis off of planning and places it on reflection. A lot of programs and methods for being more productive in school, work, fitness, and entrepreneurship place too much of an emphasis on planning. People get caught up in “analysis paralysis” and struggle to take the key actions that are going to drive success.

And this is natural. It feels good to write up some awesome plan on how you’re going to lose weight or learn a new skill, detailing different exercises you’ll do and how you’ll stick to some strict regimine. But when it comes to actually acting out these plans, we often realize that we were too ambitious with the initial plan of attack.

Letting ourselves miss a few reps turns into missing a day, and then a few days, and then a week, and before we know it, we’re quitting the program altogether (I’m looking at you, New Year’s resolutions).

Don’t get me wrong, planning before jumping into large projects is still valuable. I’ve found that a short phase of metalearning before a large undertaking gives me the best results in both the short and long term. The main problem with planning at the beginning of a long personal development journey is that we have the least amount of knowledge and experience at the beginning of the journey where we are most likely to undergo a “planning phase”. This means that the initial plan we develop at the start of a goal is made when we are most naive. That’s problematic because:

Plans and schedules only tell us about the life we’d like to have. Logs tell us about the life we’re living.

Shifting over to reflective thinking can be painful because it involves looking only at the reality of what happened. It leaves no room for delusions and talk, just action.

Let’s fast forward a few years to Janurary of 2020. This was the beginning of my last semester of undergrad at Columbia University and my primary goals changed a lot from what they were in high school. I’d set my sights on working with code, learning as much as I could about data science and artificial intelligence, and getting a job in that domain.

The natural thing to do was set out a battle plan for how I’d spend the semester and set a list of objectives for the next 4-6 months (I’ll talk more about drafting up plans in a future post). And, I decided to bring back the “training log” strategy, except this time, I’d be using the log to track my time spent doing deep work rather than time spent bodybuilding.

Deep work is a concept I heard about from Cal Newport, a famous author and computer science professor at Georgetown University. He describes deep work as

”Professional activity performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that pushes your cognitive capabilities to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skill, and are hard to replicate.”

According to this definition, shallow work mst refer to things like bouncing between email inboxes, wasting time in meetings you don’t really need to attend, and glancing at text or social media notifications. Cal Newport describes shallow work as

”Non-cognitively demanding, logical-style tasks, often performed while distracted. These efforts tend to not create new value in the world and are easy to replicate.”

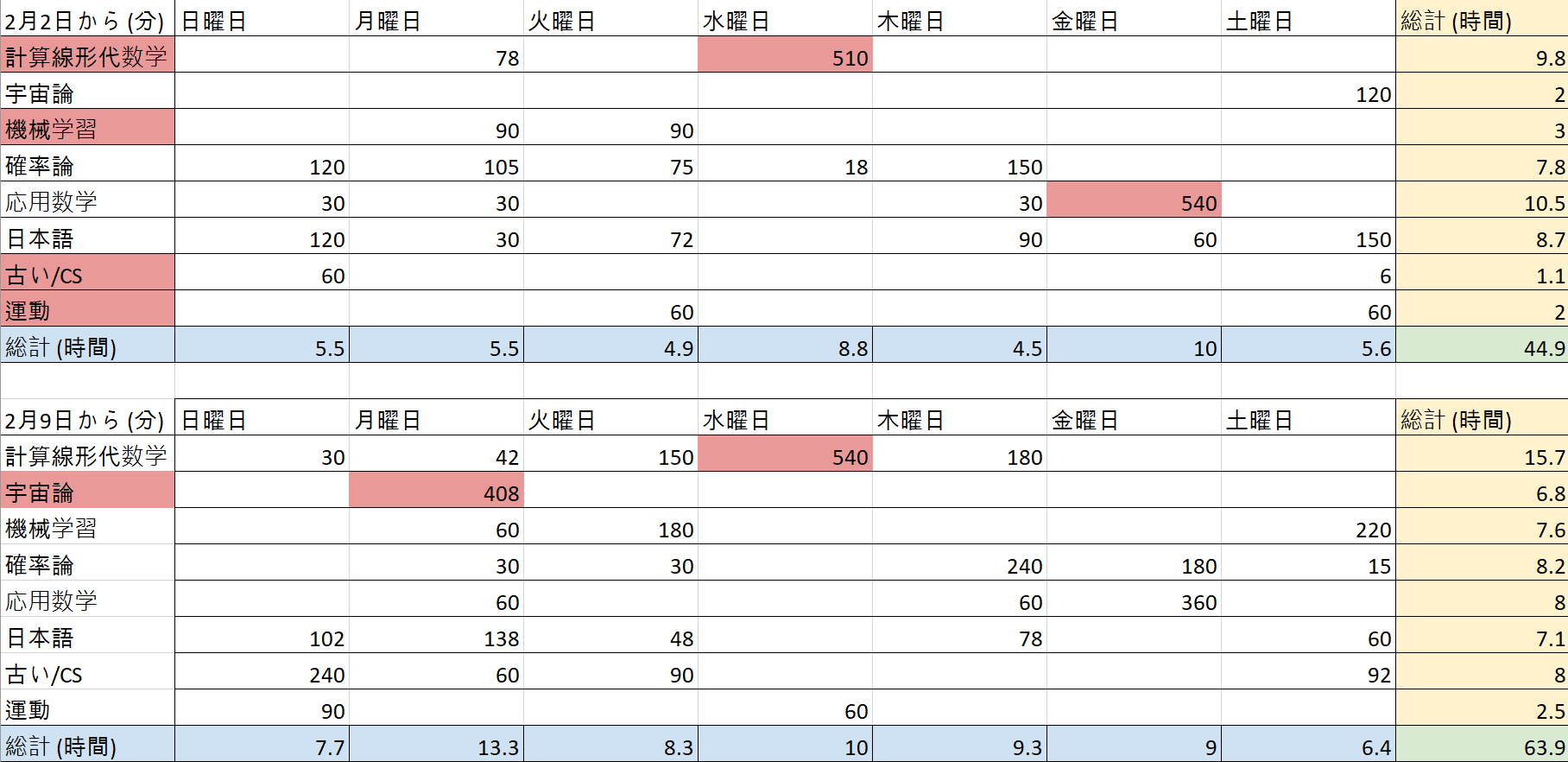

Since my new deep work training log didn’t account for shallow work, I could not count time spent in lecture, time spent in office hours, time spent “studying” near friends (where I’d end up socializing probably 40-100% of the time), or time spent doing any other passive form of learning/practice. I noticed that by taking a record of only deep work, filling up the log became a sort of game I’d play, where I’d try to accrue as much time spent doing deep work as possible. Here’s the log for the first few weeks of class that semester:

Toward the beginning of the year, I broke up the categories based on my coursework and short-term goals. In the above picture, the rows are the categories and the columns are for each day of the week. I had a category for each course I was taking in addition to one for active Japanese studies (日本語), one for programming (古い/CS), and one for exercise (運動). There’s an aggregate total number of hours along the bottom for each day (blue) and along the right side for each category (yellow).

How to use the log

Keeping this log helped me gain a sense of which areas were being and which ones needed improvement. I’d go back at the end of a week to highlight these areas and then iteratively used my own past data to inform future decision-making.

It’s healthiest to think of the log as a brutally honest tool for a diagonistic. Procrastination and failures of effort are diseases. In my psychological space, we don’t fail when something goes wrong. We fail when our effort is not at the level it needs to be.

Never worry or beat yourself up about things that are not in your control. Look at yourself as an imperfect being that needs work, but at the same time, love yourself.

I realize that a lot of this is easier said than done. The log’s purpose is not to shame you for being imperfect. There’s no such thing as being perfect. Instead, it’s healthier to think in terms of giving a perfect effort.

Logging is simply going to help you have a clear understanding of what went wrong, why things went wrong, and how you need to change your thinking in order to accelerate progress and fix and/or prevent problems in the future.

I’d constantly ask myself the following questions while reviewing my activity log:

- How can I spend the same or less time to accomplish better results?

- Am I really commiting to diligent focus during deep work sessions? And if not, how can I further develop my focusing skills?

- Did I spend the most time on the tasks that generate the most value?

- What activities can I cut out that are not helping me grow, not pushing me toward my goals, or not making me happy?

- Which activites most raise my human capital, make me feel fulfilled, and add value to other people’s lives?

Throughout the semester of tracking in this manner, I noticed over time that I could accomplish more in less time. And, I could stand to spend more time doing so. Both efficiency and endurance improved.

I also noticed that 9 times out of 9, whenever I had too many things on my plate in a given week, it was preceded by obvious negligence in a particular area. For instance, if I had to pull an all-nighter to spend 18 hours perfecting a coding assignment or a lab report, the log would show that I neglected working on anything related to that class for as long as a full week (or more).

I could see concrete evidence to support that I was often my own worst enemy through the many creative ways I’d end up shooting myself in the foot.

So, I stopped.

A concrete example: What changed for me?

Let’s fast forward a few months up to the present day (currently the end of September 2020)…

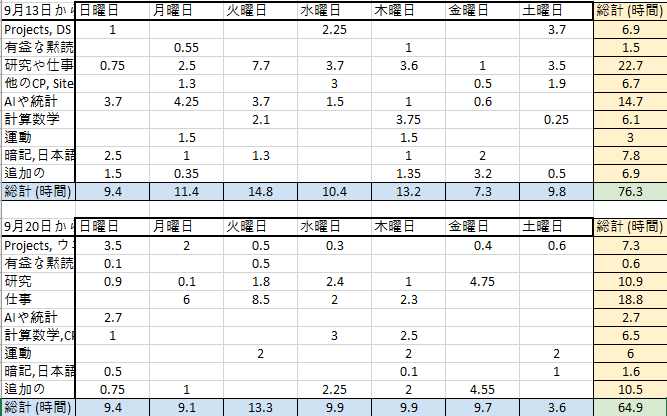

You may have noiced that the categories on the left are much different. That’s because my priorities changed quite drastically since the onset of the year. A lot of this had to do with the bulleted questions above and changes I made after reflecting.

Major Change 1: Logging Shallow Work

I added in a “supplementary” category (追加の) to track inevitable shallow work tasks such as running errands for family members, paying bills, responding to important emails, doing taxes, filling out forms, etc. This curbed feelings of guilt associated with tasks that weren’t directly related to my craft yet still had significant impact. It didn’t make sense that I’d feel bad about taking care of “regular life stuff”, so I found a compromise: Shallow tasks could still be logged as long as I gave them absolute focus and a respectable effort.

Major Change 2: Viewing the Activity Log as the Measurement of a Quantum State

This isn’t as complicated as it sounds. In quantum theory, predictions made are generally stochastic, or probabilistic. Often, the probability of obtaining certain observable outcomes is described instead of a prediction using definite values. Here’s a non-quantum, concrete example about this concept:

If you’ve ever listened to a bus or train announcement you know that it’s possible to get more than none, but far less than all, of the information you’d like. For example; after an announcement you may decide that there’s a 70% chance the train is late, a 25% chance it’s on time, and a 5% chance that someone with a crippling speech defect has violently taken over the PA system. This is a partial measurement, because a full measurement would take the form of 100% probabilities. As in; “the train is definitely, 100%, late”. - askamathematicician.com

Advice from other people, while useful, only tells us uncertain, probabilistic information. It is only when we try things out for ourselves that our information becomes deterministic, i.e. 100% certain [1].

I’m not suggesting that you ignore advice and carry excessive skepticism against the recommendations of others. I’m simply suggesting that you look more at how your “measurements” inform your future because The future is uncertain, while your measurements (past experiences) are not.

I applied this ideology when I decided to stop forcing myself to do things that people theorized would be good for me and looked more at my experimental data and the conclusions I found from working on projects first-hand.

- No more close readings of textbook on the first pass: I, like many others have been told to read things closely and take notes which can later be reviewed. This is great advice for retention in absence of potential time constraints.

- No more taking courses on topics that don’t excite me: Any course that contains material I couldn’t see a direct application for

- No more sleeping at conventional times just because other people do so: I sleep whenever I’m tired and I have my work done. If I’m ahead of schedule and feel like binge-watching psychological thriller anime at 3am, I do so.

- No more theoretical foundations in statistics: Beginner data scientists are often taught to learn calculus, linear algebra, probability theory, some foundational programming, and of course, the theoretical underpinnings of statistics. Because of my background in physics, I only needed to focus on programming and statistics. I have not yet found much utility from learning STAT 4001, the introductory graduate statistics course at Columbia University. It was only when I found a problem that warranted the usage of techniques such as hypothesis testing and comparing categorical variables with chi-squared coefficients that I began to appreciate the tools I previously learned about. And none of that mattered unless I could implement everything in code. As a beginner, data science ended up being 95% programming in my experience, which was not in line with the narrative I’d often been told.

- No more physics: Sorry, Physics. Your time has come and gone. We had fun. I like building and creating stuff too much to study fundamental, physical truths of reality. Coding feels more like music and art to me.

Basically, just try to cut out work that you know you’re not interested in. That worked for me, but I had to be patient and wait until that was something I could do without jeopardizing my future. Please don’t quit your day job or drop out of school to become a SoundCloud rapper because of this article (unless that’d make you happy 😉).

Footnotes

- Your past experiences are still not 100% certain if you live in a simulated reality. Or if you were drunk… Or if you’ve been hallucinating.

- There’s a song titled “On Reflection” that was revolutionary for its time: Wikipedia description. Link to song. I found out about it while deliberating what to title this blog post.